Stripping a relic: Moffett Field’s Hangar One, Bay Area’s most famous skeleton, nearly naked

When viewed from Highway 101, the deconstruction of Moffett Field’s Hangar One resembles dozens of white ants tearing the flesh off a metal caterpillar.

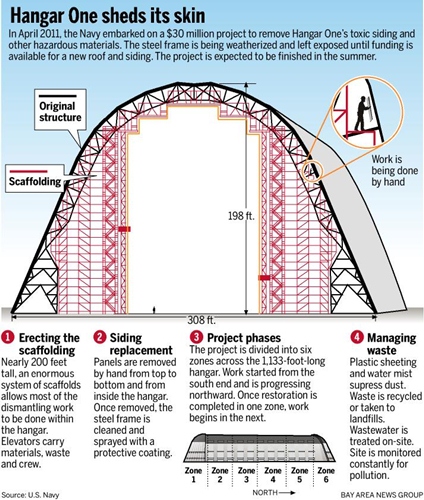

For the last nine months, workers rappelled down the outside of the hangar to remove sections of contaminated steel and redwood siding. In the next few weeks, the hangar will have morphed into a huge steel skeleton, which it will remain for the foreseeable future, frozen in time by weather sealant and government indecision.

“It’s looking real good,” said Bernard McDonough, a docent at the nearby Moffett Field Museum. “We’re surprised how nice it looks.”

The view is also great for the workers who can be as high as 20 stories off the ground.

“You can see a lot,” said Greg Jarzynsky, a safety specialist who spends 10 hours a day more than 100 feet off the ground. “Some days you can see to San Fran and just about to the Bay Bridge.”

The 79-year-old hangar’s walls and roof contained polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), asbestos and lead paint. In 2003 NASA determined that the hangar was leaking PCBs into storm drains and a nearby stormwater basin. While NASA now owns Hangar One, its former owner the Navy is responsible for cleaning it up.

One of the biggest scaffolding jobs in the history of the West Coast required months of planning, coordinating subcontractors to safely remove and dispose of Hangar One’s toxic skin, Navy contractors say. The local workers have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to work on this iconic landmark.

Opened in 1933 to house the USS Macon, one of history’s largest dirigibles, Hangar One is long and wide enough to fit six football fields and so tall that fog forms near its ceiling. To construct such a leviathan, the original builders used an enormous, movable wooden wall supported on eight railroad flatcars that traveled on railroad tracks.

This time around the Navy opted to use towering, reusable scaffolding, weighing more than 4.5 million pounds, to meet today’s strength and safety requirements, and to better intertwine with the skeleton of the building.

Seventeen tiers of wood and metal tower more than 140 feet tall. And workers have to use harnesses to ensure that they don’t fall out the exposed walls of the building. Near the top are three tiers of plywood platforms suspended by chains from the ceiling.

“The logistics of it has been a challenge,” said Mark Maniaci, construction manager for AMEC, an international engineering contractor with headquarters in the United Kingdom that is in charge of removing the hangar’s skin.

After contractors finish with one section, they can deconstruct the scaffolding and reconstruct it for another section, while simultaneously working on other sections. “Everything’s going on at the same time,” Maniaci said.

Workers use pressurized water to clean the steel girders supporting the structure. The contaminated water, as well as rainwater, is collected by a man-made dike on the floor and in a trench surrounding the hangar. There it’s pumped out, treated and tested, before it’s ejected into Sunnyvale’s sanitary system. Only 41,000 gallons have been discharged so far, a pittance compared with the wastewater discharged by Moffett Field’s NASA Ames Research Center, Maniaci said.

After being cleaned, the girders are sprayed with a protective coating that protects the exposed steel from the elements.

Then the siding comes off.

At first, workers stood on platforms that hung from the top of the building, but one side would ride up higher than the other when it was pulled up the curved hangar doors.

“The guys would spend an hour trying to get over the windows,” Maniaci said. Eventually, the deconstruction crew decided they were comfortable being supported only by a harness. “They had no fear working off the ropes,” he said. Using a harness called a boatswain chair, workers can sit down while still working.

After that, it was a breeze.

Dangling more than a hundred feet off the side of the building, workers remove panels of the steel siding that weigh between 30 to 70 pounds each and lower them to the ground using rope. At higher levels there are additional layers made of California redwood, which they remove and pass through the skeleton to workers on the inside scaffolding.

Dangling more than a hundred feet off the side of the building, workers remove panels of the steel siding that weigh between 30 to 70 pounds each and lower them to the ground using rope. At higher levels there are additional layers made of California redwood, which they remove and pass through the skeleton to workers on the inside scaffolding.

Subcontractors will remove 700,000 board feet — about 1.6 million pounds — of redwood siding. The subcontractor NCM Group, headquartered in Brea, will shave off the lead paint and PCBs to decontaminate the lumber and then sell it. Maniaci said the metal couldn’t be recycled without severely weakening it, and 1.3 million pounds have already been shipped in airtight containers for burial at the Grassy Mountain landfill in Utah.

The effort, costing upward of $30 million, will finish removing the hangar’s skin in about a month, said Bryce Bartelma, Navy project manager. Contractors will be on the job, cleaning up and coating the bottom portions of the metal skeleton until September.

After that, the future of the Bay Area’s most famous skeleton is uncertain.

Google executives Larry Page, Eric Schmidt and Sergey Brin have offered to cover the cost of putting a new cover on the hangar, in exchange for using part of it to house their eight private jets. But NASA has yet to respond.

While he would like to see it fully restored, McDonough says the nude hangar is hardly an eyesore.

“As a skeleton, it’s a really beautiful piece of work,” he said. “With the skin off it’s really a wonderful place.”